My beloved Creativity Catalyst course is now underway, and I’ve decided to play along — that is, I’m planning to try out some of my own writing prompts each week here in my paywalled garden. Each of the six weekly modules poses a creative imperative that I’m eager to heed:

Tell your story

Play with poetry

Be dramatic

Move around

Make stuff

Mix in metaphor

It can be scary, I know, to send your writing experiments out into the world for other people to see. But that’s exactly what I’ll be urging the Creativity Catalyst participants to do week after week, albeit within the safe space of the course’s gated membership area (and only if they want to) — so I’m going to walk the talk and join the vulnerability parade.

This week, I skipped ahead to Week 5 and mashed together two prompts, called “Juxtapositions” and “Layerings,” to create my paper collage for this post. The many juxtapositions and layerings of imagery, color, and form — apples, stargazer lilies, golden orbs, an ornate garden gate, a ready-to-bud David Hockney tree — are still jostling and settling in my mind. Perhaps my rough-but-resonant composition is emblematic of the Creativity Catalyst itself, with its gated content and disruptive energies? Or maybe it gestures towards a liminal moment of arrival and entry? I guess I won’t know until I write about it. . . .

But let’s not go there today. Instead, I invite you to accompany me on a quick guided tour of the marvelous Creativity Catalyst Showcase that we assembled at the end of the course last year — or you can check it out on your own. Warm thanks to Amy Lewis for curating the Showcase and to all the amazing participants from around the world who granted us permission to exhibit their writing experiments in public.

Intrigued? Inspired? There’s still time to join this year’s Creativity Catalyst! Why not treat yourself and your writing to an eye-opening, intellect-sharpening, soul-expanding elixir of creative joy?!

Step into the Showcase

To get the most from the Creativity Catalyst Showcase, I recommend that you click into each of its six Galleries in turn and spend some time exploring the exhibits there.

But life is short and we’re all very busy, so I’ve selected one exhibit from each of the galleries to highlight here — making some tough choices along the way, as there were so many treasures to savor. Enjoy!

Tell your story

The Story Gallery showcases some of the powerful non-fiction produced by Creativity Catalyst participants when they brought core elements of storytelling such as character, setting, and plot to their academic and professional writing.

Emily (USA) used the genre of detective fiction to revise an article on the challenges of learning to meditate:

I liked the idea of “Detective” as a genre. The original article says:

“At first we engage with our practice through words, yet, in no time at all, discover words are not enough. The Zen student finds they are being asked to hear meaning with more than just the ears, and somehow produce an answer beyond words.”

My first stab at a detective-like feel was:

“The student eyed the teacher warily. It seemed like this standoff had been going on for years. In fact it had — though this particular battle was only moments in the making.”

But since this doesn't say enough to resemble the original article I added more details:

“The Zen student eyed his teacher warily. The scent of incense hung in the air in the small, softly lit space. It seemed like this standoff had been going on for years. In fact it had — though this particular battle was only moments in the making.”

Play with poetry

The Poetry Gallery demonstrates how writers from any discipline or genre can use poetic language to think more creatively, write more vividly, and connect with their readers more effectively.

Vanessa (Switzerland) wrote this evocative poem as a tribute to her years of fieldwork in Ghana:

SALT

Chains on a vessel

He skips a beat

It’s just... you know... back in the day

Now it’s fish they ship away

A pool of blood

A moonless night

Such tenderness

Your light shines bright

The open sewer

The tuna stench

Their graceful posture

My back on that bench!

Mornings at the navy base

The fiery star’s hot kisses

Lucky me, I said – who said?

Theirs is work no one misses

Traffic, more traffic

The road never ends

Under the madman’s strict orders

The black man’s back bends

White skin, black magic

Whose photo is that?

Don’t try it with logic

Don’t eat that bat

Fieldwork is sweating

The big stuff, the small

It’s learning to sit with

The ache of it all

Fieldwork is heart work

Sometimes it’s fun

And always in Ghana

The sun, the sun.

Be dramatic

In the Drama Gallery, you’ll find an array of experiments with dramatic techniques such as dialogue, scriptwriting, and role-playing, all aimed at uncovering the human heart of a story.

Jasmine (Aotearoa New Zealand) brought in visual elements to ramp up the drama, “staging a scene” both figuratively and literally:

This created image was inspired by one of Helen’s experiment prompts: “Regulars in a Bar” could possibly show my struggle of diving into the various philosophical worlds for my PhD study. Instead of imagining those representative figures of different schools gathering in my mind, I decided to visualise them and let them have some “real” fun together while enjoying the alcohol. The incongruous splendour reflects the collision and confluence of varied ideologies.

The figures from left to right are Nietzsche, Adorno, Foucault, Marx, Barthes, and Derrida. By the way, the name of the bar is “Soul.”

Move around

The Moving Gallery, as its name implies, is a place of motion and emotion where writers move their own bodies through space and nudge their readers into new ways of thinking.

David (Norway) was inspired by this week’s prompts to highlight the sensory details in a series of interviews with victims of violent crime:

Memories were often expressed in visual terms: “What I remember is the tragedy […], a city in flames and constant alarm. A time of not knowing when there would be another attack, another bomb; the sensation of going out in the streets and finding corpses lying there” (male schoolteacher, late 40s).

Memories were also connected to sound: “there was the noise of the bombs and the ambulances around the city all the time; there was constant tension” (taxi driver, early 50s). Smell also played a significant role in the accounts of direct witnesses: “I remember going to school […] and there were corpses there, I could smell the blood, but I had to keep walking because I did not want to see if the body was of someone I knew” (unemployed man, early 40s). Intertwined with memories of suffering were recollections of considerable economic activity: “a lot of pain, a lot of fear, many murders, but also a lot of money” (housewife, late 60s).

Make stuff

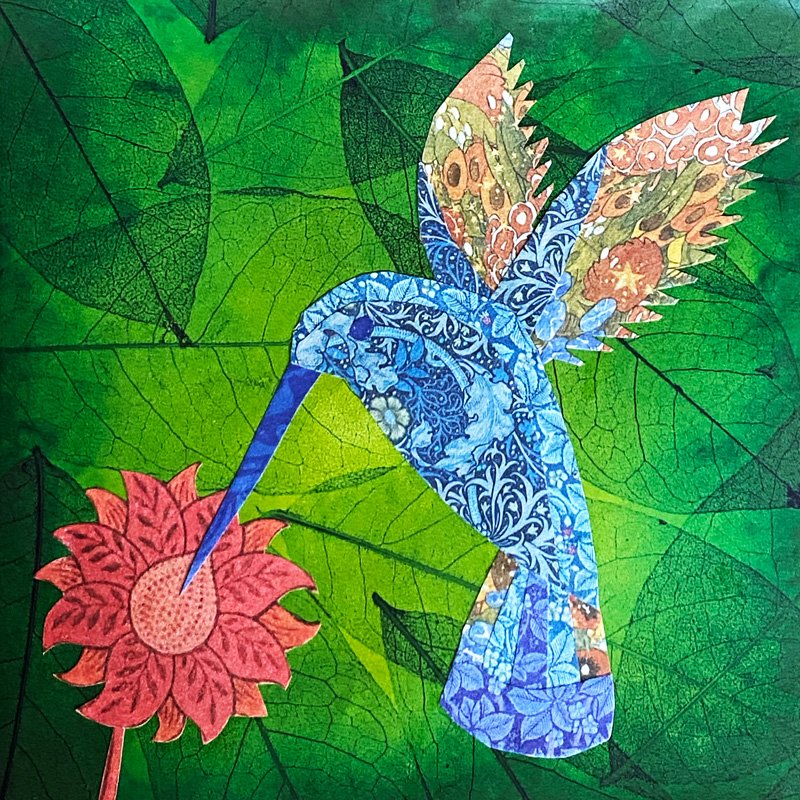

For the exhibitions in the Making Gallery, participants turned off their digital devices and got out paper and scissors, colored pencils and glue. They let their hands tell them what and how to write.

Catalina (UK) used the intersecting genres of paper collage and poetry to reflect on the interplay of mapping, making, and emotion in her disciplinary area of urban planning:

Maps cultivating gut feelings

Writing as storytelling

Connecting the emotions of the mundaneWriting as visual poetry

Layering meaning and beautyWriting as dramatic plot

Revealing the epic tensions of everydayWriting as embodied movement

Dancing lines of thoughtWriting as metaphorical craft

Turning lame into velvetWriting, a golden thread stitching

the hand playing with shapes and imagesthe heart beating words

the mind weaving ideas

the body breathing meaning

Mix in metaphor

In the Metaphor Gallery, we witness vivid demonstrations of how metaphors can convey complex ideas to readers and help writers re-story their own emotions.

Patrick (USA) used the metaphor of boxing to reflect on his own fraught relationship to the writing process:

When I am writing at my best, I would say I am a boxing contender on the night when they become champ. The document is an opponent that has possibly underestimated just how prepared I am for the moment. I am walking my opponent into the punches I want to throw. I am not reacting but rather I am dictating the terms of engagement. I am leading the dance so to speak. To think about the metaphor during times when I am not writing well, I am just reacting. I am being walked into traps—traps in the literature and traps in the individual sentences. It is at those points that I am not quite clear how I got into a corner and I don’t know how to get out. I am fighting at my opponent’s pace, while I can win fight their pace (getting something written that can be published), I am not usually pleased with the outcome. I only got stuff done but I did not necessarily excel. . . . When I am loving writing, I am in a groove. I am seeing the punches before they are thrown. I am able to side-step and account for anything that is thrown at me. I am also able to riff. When I get stuck writing, I have the most success when I go back to the basics. In boxing, it’s how do you throw a 1-2 or a jab and right hand. When I am stuck, it’s about getting back to writing simple but clear sentences.

This post was originally published on my free Substack newsletter, Helen’s Word. Subscribe here to access my full Substack archive and get weekly writing-related news and inspiration delivered straight to your inbox.

WriteSPACE members enjoy a complimentary subscription to Helen’s Word as part of their membership, which costs just USD $12.50 per month on the annual plan. Not a member? Sign up now for a free 30-day trial!